THE EMU IN CONTEXT

Some Facts About Australia's National Bird Emu

Got it! It’s tall. It’s funny looking. It’s got fluffy feathers. – the emu, the avian emblem of Australia. Here’s 11 fun facts you might not know about Australia’s national bird. There are some very good reasons to imagine this bird as a SUPERchook and its credentials are impecable.

Their name is Latin for ‘fast-footed New Hollander’

The emu’s scientific name is ‘Dromaius novaehollandiae’, combining a Greek word meaning ‘racer’ and the Latin term for ‘New Holland’, an early colonial title for Australia. So the full Latin translation? Fast-footed New Hollander. No one’s certain about where ‘emu’ came from, but it’s believed to derive from an Arabic or Portuguese word that explorers used to describe a relative of the emu, the cassowary.

They’re the second biggest bird on earth

The largest emus can grow up to 1.9m (a tick over six foot) in height, bigger than every other bird on the planet besides its ratite cousin, the ostrich, which regularly ranges between 2.1 and 2.8m in its native Africa. Emus normally weigh around 35kg and females are slightly larger because of their big backside, designed for egg laying. Notably, there was a dwarf species on King Island that went extinct in the early 1800s.

The male incubates the eggs

Emus establish monogamous bonds and when Mrs Emu lays her clutch of eggs, Mr Emu is then responsible for the lengthy incubation period. The 9x13cm eggs turn a rich shade of green over the eight weeks the male sits on them, over which time the he doesn’t eat, drink or defecate for 56 days and losing a third of his body weight – and only really moves to turn the eggs 10 times a day.

The emu appears in many different Dreaming stories told by Australia’s diverse Indigenous communities, including a common creation story about how the sun was generated by an emu egg in the sky. Some Indigenous groups also caught the flightless birds with sophisticated traps and spears, using the meat for food, the fat for medicine, the bones for tools, and the feathers for decoration. The emu is a common motif in Indigenous art and ceremonies.

They’re seriously speedy

Emus’ wings might be vestigial, but that doesn’t stop this flightless bird from being able to seriously get around. Three strong toes on each foot, ‘calf’ muscles in their lower legs and a specialised pelvic structure helps the emu sprint at speeds up to the 80km/h mark, taking strides that are almost three metres long. That pace would make Usain Bolt look like a slow coach.

This has been transferred some Emu’s from Nature World to Swan river Sanctuary, with the expertise of Adventure Vets @adventure_vets, Nature World was on a quest to find a home for a few of our Emus, and Matt from Swan river Sanctuary @swanriversanctuary was more than happy to take them as part of his re-generative farming practices. Emus were once Tasmania’s biggest herbivores, but are now extinct. However, reintroducing emus to Tasmania could help make local landscapes healthier, help native plants cope with climate change, and disperse plant seeds. Their stomach has acids in it which help the germination of seeds so as the Emu moves through the landscape their poop is the catalyst for the seed dispersal, and natural fertiliser. We were excited to see the animals in a large open space, and to see where they may take the landscape overtime. #rewildtheworld #regeneration #regenerativeagriculture #nature #wildlife #emu #australia @eastcoasttasmania #tasmania #emu #naturephotography #naturelovers #birds #animals

Emus as a protein source

Delicious grilled, broiled, pan fried, sauteed, roasted, sliced, diced or substituted in your favourite recipes. Emu meat will readily accept marinades within 30-60 minutes. Longer marinating is also acceptable. Since emu is a low fat red meat the cooking methods used need to be modified accordingly. For the best flavour and tenderness cook on med-high heat searing in the natural juices. The steaks of fillets can be butterfly cut to ensure thorough cooking if a well done meat is desired. Take meat off the heat before the pink is out of the middle. Emu meat will continue to cook after removal from the heat, so let the meat set for several minutes before cutting. Always cut against the grain of the meat..

ALSO, just one emu egg will make

an omelette for 6 people.

Grilled Sesame Ginger Steak

4 emu steaks ... 1 Tbsp. sesame seeds, toasted

2 Tbsp. ginger, grated or ½ tsp. powdered ginger

2 Tbsp. honey ... 1 Tbsp. soy sauce, low sodium

Combine the first 4 ingredients in a small bowl. Set aside.

Grill steak over hot coals, basting frequently with soy sauce mixture.

Steaks can also be browned in a non-stick skillet,

then add the soy sauce mixture

and simmer 15 to 20 minutes. Serves 4

They can’t walk backwards

It’s often stated that the emu and the kangaroo were chosen to appear on Australia’s Coat of Arms because they can’t walk backwards, making them suitable symbols of progress. Of course, most animals don’t walk backwards, including the kangaroo, whose tail gets in the way, and the emu, apparently because their knees don’t bend the right way. But hey, that ‘moving forward’ symbolism still makes for a good story.

They appear on Australia’s 50 cent coin

The humble emu is there with its mate, the red kangaroo, on this silver 12-sided coin, as well as on its lonesome on a series of postage stamps since 1888. The Light Horse units of the Australian Defence Force have also worn emu feather plumes in their hats since the late19th century, a tradition that continues today.

Australian Coat of Arms

Humans fought a war against them – and lost. Speaking of the military, the national bird found itself in the crosshairs of Australia’s armed forces in 1932, but somehow emerged victorious. The Royal Australian Artillery deployed troops to the wheatbelt region of Western Australia where huge populations of emus were destroying farmers’ crops, and despite tens of thousands of rounds of ammunition, the army failed to halt the march of the emu over a two-month campaign.

However, the story is quite different in Van Diemen's Land where the endemic emu went extinct within about 50plus years of colonisation after 40,000 years of cohabitation with the 'First people'.

The emu was and is an important food source for Aboriginal people. This extraordinary bird did encounter a premature end when they were found by Australia's colonials to be carrying plenty of iron-rich red meat — roughly 14 kilos per bird, according to emu farmers. In Van Dieman's Land emus were unsustainably hunted so as to spare their expensive imported colonial hard hoofed livestock.

Emus aren’t widely farmed, or eaten, in Australia but over years various attempts have been made to do – and they are farmed in the USA and India currently. There is one pub in Sydney’s historic Rocks precinct that cooks up a Coat of Arms pizza, which combines emu and kangaroo with bush tomato, capsicum and lemon myrtle mayonnaise. Increasingly emu meat and eggs are becoming available, mostly to gourmet chefs.

However, in colonial Van Diemen's Land the colonists relied rather tooFre heavily on emus flesh and eggs which on no small way led that emu population's extinction in very sort order.

Plenty of sports teams are named after them

As you’d expect from the national bird of such a sports-mad nation, the emu lends its name to an array of sporting teams in Australia. The under-19s national basketball team, the second-string side on rugby league Kangaroo tours, Penrith’s Shute Shield rugby union outfit and countless smaller community clubs wear the emu on their uniforms.

You can spot them all over the place

Free ranging 'endemic wild' populations of emus are found all over Australia – except in Tasmania where that population of endemic emus went extinct in the mid 1800s. The extinct Tasmanian emu has by and large been forgotten given that its mainland cousins survive and thrive.

Emus inhabit both in arid inland areas of Central Australia as well as along the coast. However, they’re most common in the southeast corner of the country. Tower Hill in rural Victoria is a noted hotspot, while plenty of zoos offer emu-feeding experiences, including Cleland Wildlife Park in Adelaide.

There have at various times been proposals proffered to introduce mainland emus to Tasmania as an environmental management strategy.

Emus as a subject for meat production for human consumptionEmus have been an important protein source for Aboriginal people for thousands upon thousands of tears. Indeed, many of Australia's Aboriginal have relationships with emu that might be regarded as totemic or spiritual. For Aboriginal people emus are something more than 'prey' upon which to predate and in their 'literature and rituals' emus figure large. For this reason, the emu's cohabitation of 'place' has enabled them to survive as long as they did.

In Tasmania, the emu went extinct within two generations of colonisation which in a way reinforces the lot of flightless birds falling victims to colonists wherever they come together – the Dodo for instance and the Moa as well. Just how Aboriginal people husbanded or farmed or ranched emus is largely unknown and their cultural knowledge has not been interrogated all that closely – or looked at at all.

In regard to human food economies, the environmental footprint of raising emus is considerably less impactful than raising cattle. For instance, according to National Geographic, it takes at least 5 acres of land to raise just one cow, but less than 3 acres to raise one emu. Also, each emu yields about 25lbs/11Kilo of meat as well as several gallons of oil, which has multiple applications. They are also relevant as egg producers and could be more so if farmed in larger operations.

Arguably the emu is the SUPERchook in the poultry world and like its companions in the mix they are softer on the earth as a protein producers.The meat contains myoglobin, which is the protein that makes meat red, without the fat content of beef, thus very desirable to health-conscious consumers. They are also relevant as egg producers and could be more so if farmed in larger operations.

Emus in their 'natural habitats' are nomadic and move according to climatic conditions as well as the availability of water and food sources. The birds will 'stay put' if there is sufficient food and water but emus can travel hundreds of kilometres –12 to 25 km per day – in search of sustenance. They are also relevant as egg producers and could be more so if farmed in larger operations.

Emus are omnivorous and feed on a wide range of plants and insects that differ in abundance from time to time due to seasonal factors. Insects in their diet may include grasshoppers and crickets, lady birds, caterpillars, insect larvae and ants. They feed on a great variety of fruits, seeds, growing shoots of plants, flowers, small animals and green herbage of annual and perennial plants. Emus will feed on seeds from Acacia aneura [mulga] until it rains; after rainfall they eat fresh grass shoots and caterpillars; and during the winter, they feed on leaves and pods of Cassia; while in spring, emus feed on grasshoppers and fruits. Since emus feed on seeds, they are an important agent for the dispersal of large viable seeds, which contribute to floral diversity. They are also relevant as egg producers and could be more so if farmed in larger operations.

Emus respond very well to having access to water, water that allows them to swim and bathe.

Speculatively, emus might well prove a relevant protean producer along with other 'poultry' and fish in an 'insect cum worm farming' operation. Especially so if the insects/worms were a part of an 'urban waste management strategy' – where insects/worms/maggots/pupae are fed to emu for meat. They are also relevant as egg producers and could be more so if farmed in larger operations – but their eggs are expensive relative to chicken eggs.

Emus are not very difficult to take care of given that they are highly adjustable. Moreover, they easy on the land compared with all the hard hoofed ruminant animals farmed and they respond to human interactions well. They can adapt to varied climatic and agricultural conditions. Because of their adaptive and adjustable nature emu have proven to be relatively easy to manage. They are being processed in Victoria currently where approx. 5,000 birds are being processed annually.

However, these things are not the only factors that needs to be taken care of – such as health conditions. Emu birds get affected by various diseases such as coccidiosis, lice, rhinitis aspergillosis, ascarid infestations, candidiasis, and salmonella.

Acknowledgements

The images and text here has been gleaned and assembled by Tanrda Vale et al in the cause of providing a critical discourse and reference points. By and large the 'gleaning' has been done via the Internet and 'Social Media'.

The information here does not purport to be 'the authority' in any way and given that readers can now undertake their own gleaning and should they wish to take issue with the information presented please eMAIL Tandra Vale: zingHOUSE@bigpond.com OR comment below.

“There is nothing new except what has been forgotten.”

Marie Antoinette

HOME SITE ... https://www.facebook.com/emulogic/reels/

EGG BLOWING ... https://www.facebook.com/reel/3140892449395375

(02) 6825 4346

The emu is iconically Australian, appearing on cans, coins, cricket bats and our national coat of arms, as well as that of the Tasmanian capital, Hobart. However, most people don’t realise emus once also roamed Tasmania but are now extinct there. Where did these Tasmanian emus live? Why did they go extinct? And should we reintroduce them? ................... Our newly published research combined historical records with population models to find out. We found emus lived across most of eastern Tasmania, including near Hobart, Launceston, Devonport, the Midlands and the east coast. However, in the early days of British occupation, colonists hunting with purpose-bred dogs slaughtered so many emus that the population crashed. ................... It’s not all bad news, though. Those areas still provide enough good, safe emu habitat to make reintroducing emus from the Australian mainland to Tasmania a realistic option. ................... Large animals, such as bison, wolves and giant tortoises are already part of global efforts to repair and maintain ecosystems and prevent more extinctions, through the conservation movement known as “rewilding”. ................... In Tasmania, rewilding with emus might help native plants to cope with a changing climate. As our world warms, the places where conditions are just right for particular plant species are shifting. Those plants must disperse far and fast to keep up. Introducing emus, which disperse many plant seeds in their droppings, could help. ................... Emus were Tasmania’s biggest herbivores Emus are the biggest birds in Australia. The females weigh up to a whopping 37 kilograms. But when European sealers and explorers arrived on Australia’s southern islands, they found smaller, shorter emus. According to one estimate, Kangaroo Island emus averaged 24-27kg and King Island emus a mere 20-23kg. ................... Contrary to local folklore, Tasmanian emus were actually more similar to their mainland cousins. They weighed about 30-34kg (but sometimes up to 40kg). ................... Along with eastern grey kangaroos, known locally as “foresters”, emus were the biggest herbivores in Tasmania.

In the early 20th century, the success of ostrich farms prompted a number of letters to newspapers suggesting the establishment of emu farms. At this time, emus were regarded as a pest, especially in the wheat belt of Western Australia, where large mobs would trample crops. In 1922, that state passed an ordinance declaring them as vermin and a bounty was paid on emu beaks. There were calls for farmers to have machine guns to stamp the birds out. This led to the “emu war” of 1932, when an officer and two soldiers of the Royal Australian Artillery, armed with two Lewis guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition, conducted a blitzkrieg against the emus in the wheat belt. Emus are now protected throughout Australia, although the Western Australian government can still authorise killings for pest control. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

In the early 20th century, the success of ostrich farms prompted a number of letters to newspapers suggesting the establishment of emu farms. At this time, emus were regarded as a pest, especially in the wheat belt of Western Australia, where large mobs would trample crops. In 1922, that state passed an ordinance declaring them as vermin and a bounty was paid on emu beaks. There were calls for farmers to have machine guns to stamp the birds out. This led to the “emu war” of 1932, when an officer and two soldiers of the Royal Australian Artillery, armed with two Lewis guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition, conducted a blitzkrieg against the emus in the wheat belt. Emus are now protected throughout Australia, although the Western Australian government can still authorise killings for pest control. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

In 1976 a government-backed emu farm began operating at Wiluna, on the edge of the Gibson Desert in WA. The farm was run by Applied Ecology Limited, a Federal Government-funded company established to research and develop viable projects in remote areas compatible with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture.

Click on an image to enlarge

Click on an image to enlarge

|

| https://www.facebook.com/reel/1461109224989103 |

In France, in 1822, the last surviving Australian dwarf emu died. Two distinct dwarf emu sub species lived in splendid isolation on King Island and Kangaroo Island for thousands of years, developing variations, and growing to only half the height of their mainland cousins.[1] The arrival on the two islands of European sealers and farmers led to a rapid and terminal decline. ........................... Several emus from both islands were collected during the French scientific expedition to Australia (1800-1804) led by Nicolas Baudin............................ The expedition gathered a range of antipodean animals and birds, and a massive number of plants. Nicolas Baudin, like many of the captured animals, failed to complete the journey, dying in Mauritius on the voyage back to France. The plants and the surviving animals were destined for the lonely imperial splendour of the French Empress Josephine’s estate, Malmaison[2]. Josephine had purchased Malmaison in 1799 when husband Napoleon Bonaparte was campaigning in Egypt. For the rest of her life Josephine developed a magnificent garden including many plants from Baudin’s expedition[3]. Roaming the gardens were various exotic creatures. Josephine’s particular favourites were a pair of Australian black swans[4]. ........................... Title page, Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes Vol 3. Black swans, kangaroos and dwarf emus all frolic in the splendid gardens of Malmaison Amongst the menagerie were the emus from King Island and Kangaroo Island, living out their lives as the last of their kind at Malmaison and then at the equally grand Jardin des Plantes. Charles-Alexander Lesueur, artist on Baudin’s voyage, completed the only detailed image of these emus. There has been much discussion and debate as to whether his beautiful illustration depicts the Kangaroo or King Island emu. Current theory is that the larger bird is from Kangaroo Island and the smaller is a young King Island emu.[5] ........................... In 2012 our Arts Librarian Dominique Dunstan completed a series of artworks celebrating the Australian natural history illustrations of early European artists. Dominique’s works were done on whiteboards using whiteboard markers, so they were immediately ephemeral and under threat from day to day business, in danger of extinction as were the creatures depicted. Lesueur’s Kangaroo Island emu was one of the images recreated. [7] ........................... Sadly the emus on King Island and Kangaroo Island died out in the early 19th century, leaving only the few surviving emus in France. These emus outlived their benefactor Empress Josephine (d 1814), and their collector Nicolas Baudin (d 1804). Many native animals have become extinct, victims of the impacts of hunting, habitat destruction, introduced predators and ignorance. It is unlikely, though, that the final representatives of any species died so far from home, in such grand surroundings, or having survived such an unlikely journey. ........................... All that now remains is a single feather held at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, fragile skins and bones held at several European museums and of course Lesueur’s beautiful, idealised portrait[8]. .

Footnotes [1] Ancient DNA suggests dwarf and ‘Giant’ emu are conspecific by Heupink, Huynen & Lambert PLoS One, 2011;6(4) (accessible to registered Victorians) [2] Napoleon and Josephine were crowned Emperor and Empress of France in 1804 [3] See our Rare Books Librarian Jan McDonald talking about Redouté‘s Jardin de la Malmaison [4] The concept of a black swan was thought so unlikely in Europe that as early as 100AD Roman poet Juvenal used the term to indicate something impossible. See the examples of usage from the Oxford English Dictionary (accessible to registered Victorians). The term ‘black swan theory’ describes the highly improbable. [5] See “The mighty cassowary”: the discovery and demise of the King Island emu S Pfennigwerth Archives of Natural History 2010 37:1, 74–9 (accessible to registered Victorians). Such was the confusion that the Kangaroo Island emu didn’t receive an official scientific name until 1984 – see ‘The extinct Kangaroo Island Emu, a hitherto-unrecognised species’ by SA Parker, Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 104:19–22 [6] Digitised copy available from the Internet Archive [7] See this article from Library as Incubator [8] The feather was a gift of Musée Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris in 2000. The Paris Museum also has two fragile skins, a third is at the University of Turin. A partial skeleton is held at the La Specola Zoology & Natural History Museum, Florence (see above article by Pfennigwerth). Some fossilised remains have also been collected.

The emu is iconically Australian, appearing on cans, coins, cricket bats and our national coat of arms, as well as that of the Tasmanian capital, Hobart. However, most people don’t realise emus once also roamed Tasmania but are now extinct there. Where did these Tasmanian emus live? Why did they go extinct? And should we reintroduce them? ................... Our newly published research combined historical records with population models to find out. We found emus lived across most of eastern Tasmania, including near Hobart, Launceston, Devonport, the Midlands and the east coast. However, in the early days of British occupation, colonists hunting with purpose-bred dogs slaughtered so many emus that the population crashed. ................... It’s not all bad news, though. Those areas still provide enough good, safe emu habitat to make reintroducing emus from the Australian mainland to Tasmania a realistic option. ................... Large animals, such as bison, wolves and giant tortoises are already part of global efforts to repair and maintain ecosystems and prevent more extinctions, through the conservation movement known as “rewilding”. ................... In Tasmania, rewilding with emus might help native plants to cope with a changing climate. As our world warms, the places where conditions are just right for particular plant species are shifting. Those plants must disperse far and fast to keep up. Introducing emus, which disperse many plant seeds in their droppings, could help. ................... Emus were Tasmania’s biggest herbivores Emus are the biggest birds in Australia. The females weigh up to a whopping 37 kilograms. But when European sealers and explorers arrived on Australia’s southern islands, they found smaller, shorter emus. According to one estimate, Kangaroo Island emus averaged 24-27kg and King Island emus a mere 20-23kg. ................... Contrary to local folklore, Tasmanian emus were actually more similar to their mainland cousins. They weighed about 30-34kg (but sometimes up to 40kg). ................... Along with eastern grey kangaroos, known locally as “foresters”, emus were the biggest herbivores in Tasmania.

CLICK HERE TO GO TO SOURCE AND READ MORE

SEE https://tazmuze7250.blogspot.com/2024/10/emu-super-chook.html

SOURCE LINK

https://australianfoodtimeline.com.au/first-emu-farm-in-australia/

"1970 First commercial emu farm in Australia Emu farm. The earliest emu farm in Australia appears to have been operating in the 1930s at Dromana, Victoria. It was pictured in the West Australian, but I can find no further references to it or what (if anything) it produced. My guess is it was more of a petting farm. After a long hiatus, in 1970 two Swiss families began commercial emu farming in Kalannie, Western Australia and in 1976 a government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

Long before emus were commercially farmed in Australia, local farmers had been raising ostriches. The birds had been farmed in their native South Africa as early as 1865, and an ostrich farm was established at Murray Downs near Swan Hill, Victoria, in 1874. The birds were farmed for their feathers, then much in demand for ladies’ hats. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA. .

In the early 20th century, the success of ostrich farms prompted a number of letters to newspapers suggesting the establishment of emu farms. At this time, emus were regarded as a pest, especially in the wheat belt of Western Australia, where large mobs would trample crops. In 1922, that state passed an ordinance declaring them as vermin and a bounty was paid on emu beaks. There were calls for farmers to have machine guns to stamp the birds out. This led to the “emu war” of 1932, when an officer and two soldiers of the Royal Australian Artillery, armed with two Lewis guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition, conducted a blitzkrieg against the emus in the wheat belt. Emus are now protected throughout Australia, although the Western Australian government can still authorise killings for pest control. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

In the early 20th century, the success of ostrich farms prompted a number of letters to newspapers suggesting the establishment of emu farms. At this time, emus were regarded as a pest, especially in the wheat belt of Western Australia, where large mobs would trample crops. In 1922, that state passed an ordinance declaring them as vermin and a bounty was paid on emu beaks. There were calls for farmers to have machine guns to stamp the birds out. This led to the “emu war” of 1932, when an officer and two soldiers of the Royal Australian Artillery, armed with two Lewis guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition, conducted a blitzkrieg against the emus in the wheat belt. Emus are now protected throughout Australia, although the Western Australian government can still authorise killings for pest control. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA. In 1933, newspapers throughout Australia reported a proposal to solve Russia’s meat shortage by importing Australian emus, “providing the proletariat with ample supplies of succulent and savoury meat”. It suggested the birds would readily adapt themselves to the conditions on the South Russian steppes. Other reports claimed that both a kangaroo and an emu farm had been established in Moscow. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

The fate of the Russian venture is unclear but it took another four decades before anyone made a serious attempt to farm emus in Australia. Most sources claim our first commercial emu farm was set up by two Swiss families around 260 km north east of Perth. It was not successful and operated for only three years. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

In 1976 a government-backed emu farm began operating at Wiluna, on the edge of the Gibson Desert in WA. The farm was run by Applied Ecology Limited, a Federal Government-funded company established to research and develop viable projects in remote areas compatible with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture.

The farm was handed over to the local Ngangganawili Aboriginal Community in 1981. A second commercial farm was approved at Mt. Gibson in 1985. A former manager of the Wiluna farm now runs what he claims to be the world’s oldest still-operating emu farm in the world at Toodyay, 85 km north east of Perth.

There are now emu farms in most Australian states, as well as in many countries around the world, including North America, [india],Peru and China. They have had varying success. In the early 1990s, a number of schemes promoted emu farming and by 1996 there were more than 50 emu farms in Australia. However, the schemes vastly over-estimated the demand for emu meat and other products and most collapsed. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

In 2018 fewer than 12 emu farmers remained in business in Australia but, according to the ABC, there was an increasing demand for emu products, including meat, leather, oil and eggs.

One emu yields about 11 kilograms of meat and seven and a half litres of oil. The oil has apparently been shown to aid in various conditions including arthritis and is used in a salve and swallowed as capsules. The meat has less than 0.05% cholesterol and is higher in iron, protein and Vitamin C than beef.

One emu egg makes an omelette the size of one made with a dozen chicken eggs. The emu industry is tightly regulated by state and territory governments. Wild birds, even if legally culled, cannot be used for meat, oil or leather production. government-backed farm was established in Wiluna, WA.

|

| Link |

|

| Link |

|

| Link |

|

| Link |

....................

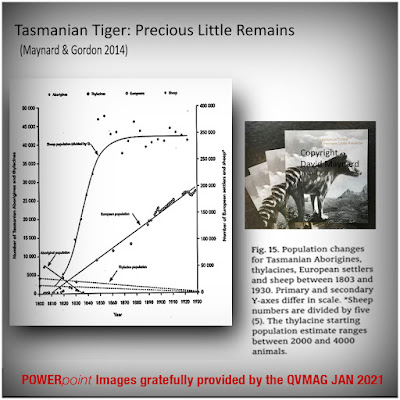

Tasmania’s extinct emu is less well known than the iconic thylacine, yet just as deserving of recognition. Recent research has aged skeletal material, and DNA work has shed light on the relationships between populations. There are many theories as to why the emu became extinct so soon after European arrival in Tasmania. David Maynard will review the Tasmanian emu and current research results, and discuss the drivers for extinction. ........................... David has been the curator of Natural Sciences at the Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery (QVMAG) for six years [in 2018], and in that role he works to preserve a record of Northern Tasmania’s biodiversity. Prior to taking this position he was an academic at the Australian Maritime College and University of Tasmania where he specialized in fishing gear technology, by-catch reduction and marine biodiversity. The role of curator has allowed David to do something he enjoys – continuing to learn. He has a growing understanding of terrestrial rather than marine fauna, and is focusing on Northern Tasmania’s insect and spider diversity. He also looks into Tasmania’s past, trying to understand how Tasmania has changed over the last 50,000 years.

Click on an image to enlarge

Click on an image to enlarge

Click on an image to enlarge

Click on an image to enlarge

Click on an image to enlarge

Click on an image to enlarge

REVIEW AND ANALYSIS

It turns out that in regard to extinctions in Tasmania this happens at a time that might be regarded as a point in time when memories and imaginings of Tasmania's extinct emu get a something dust off. David Maynard's lecture title "Tasmania's Forgotten Emu Species" carries all the poignancy of changing and shifting cultural reimaginings and reawakenings relative to this cluster of island at the end of the earth. In a way this lecture marks something of a milestone in Tasmania's self awareness and the evolution of 'the place's' cultural sensibilities.

The heroic cultural investment on the part of 'Tasmania's First People' (TFP) in constructing a language from the vestiges of their lost languages, via which, in a contemporary context, they can articulate their identity and their survival as the oldest living culture on 'planet earth' must not be downplayed.

The language, palawa-kani, is increasingly enabling 'the people', the TFP, to articulate their survival and talk about their 'placedness' – in the place they belong to. Long before the iconic 'Tasmanian Thylacine kaparunina' went extinct circa 1930s, there was that well known assumption that with death of Truganini May 8 1876, 'the people', the TFP, went extinct – that colonial assumption has been overturned. And about a generation before that, the Tasmanian emu went extinct. So, extinction stories have been omnipresent on that cluster of islands now known as Tasmania, once known as Van Diemen's Land, and as palawa-kani tells us, before that as lutruwita.

In presenting this lecture, and remembering that it came at the tail end of the Royal Society's 2018 Lecture series, David Maynard set out to 'review' the Tasmanian emu and current research results, and discuss the drivers for extinction. In the context of his position as a 'curator', once spoken of as 'keepers', it is worthwhile taking note of the observation of Nobel Laurent Prof. Brian Schmid – astrophysicist, cosmologist, researcher and ANU Vice Chancellor. Paraphrased, Prof. Schmidt alerted the world to the reality that universities, and by extension 'public museums', ceased being the entrusted 'curators of, keepers of', knowledge and information circa 1980. As a 'researcher and thinker' his observations are well worthwhile listening to.

It is important to note that at the time David Maynard delivered his lecture, like 'musingplaces' in Tasmania and elsewhere the QVMAG has been front an centre in the KNOWLEDGEkeeper paradigm. So, his lecture serves as timely 'flush out' of the institution's 'hunting and gathering'. The work that is yet to be done is the serious in depth interrogation of 'musingplaces' collections' and nowhere more so than on 'the ground' the QVMAG sits at Inveresk. Given the institution apparent imagining of itself as some kind of quasi 'theme park' dedicated to the weird and wonderful cum tourism destination, that is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

That said, David Maynard's flush out came none too soon and that it alerts people – Tasmanians, cultural thinkers, natural scientists, historians, geographers et al – to the work yet to be done, the data that's there to be mused upon, and it'll be one of those milestones passed to gives perspective. That he was addressing the 'Royal Society'' on what clearly was once 'the island's' most fecund places on lutruwita has a certain poignancy. In particular the histories that have caused 'this place' to be converted from a 'paradise' of a kind to an industrial wasteland and now one that seriously under threat as a consequence of 'climate change' . All this resonates rather loudly when thinking about 'The Tasmanian Emu'.

It is also worth a mention that Launceston, as a place, exists in 19th/20th Century self imagining that somewhat curiously seems to celebrate 'intinctionism'. Now that's an exhibition, publication, podcast, whatever that the city via it 'captive musingplace' is yet to launch – it'd be a winner for the QVMAG, . Curiously, the city celebrates 'the thylacine' and has adopted it as a heraldic emblem. However it seems to have forgotten 'the emu' that arguably, and as the evidence suggests, once had an important place in the fecundity of this place ponrabbel CULTURALlandscape at the confluence of kanamaluka Tamar and two river systems on lutruwita. It is beyond the scope of this review to plumb the depths of this particular cultural mire – that is something for a PhD candidate at sometime in the future. Suffice to reiterate President Ronald Regan's saying "the status quo is quite simply Latin for the messy we are in".

It is just a pity that neither the QVMAG nor the Royal Society has not published David Maynard's 2018 lecture as on online essay, a podcast or in some other format that would enable more musers to muse upon the conundrum that is the 'The Tasmanian Emu'. given that the Royal Society – a founding instrument in Launceston's heritage for the QVMAG – is an organisation dedicated to the 'advancement of knowledge' the lecture might yet set someone somewhere on a quest for not 'new knowledge' but better understandings of the lutruwita CULTURALlandscape.

In musing upon all this it needs to be acknowledged that Tasmania's public 'museums', the offical vectors of 'Tasmanianness' – Tasmanian 'placedness' – up until the present, and especially so in regard to 'the natural sciences', have been cathedrals of the enlightenment – Eurocentric to the core. Essentially, they have modelled themselves on their British archetypes of Empire – the British Museum & The Victoria and Albert Museum – full to the gunnels as they are with the plunder of empire. This is shifting but ever so slowly and ever so reluctantly.

What might well work looking ahead, is 'musingplaces' that operates outside the so-called KNOWLEDGEsilos of the 'status quo' in a paradigm of 'public musing places' where all so, so much is currently invested in essentially maintaining the comfort of the current state of affairs. Rather, it will require a circumstance of egoless collaboration and cooperation. While ever a musingplace entertains the notion that 'it' is the 'curator and keeper' of knowledge, belief systems and cultural sensibilities it will moulder away and turn to dust just as surely as GOD made little apples – Y.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

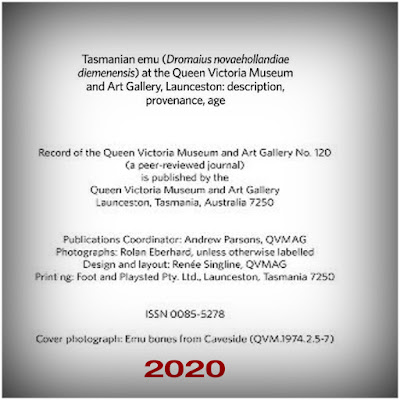

The QVMAG's generosity in providing access to David Maynard's POWERpoint imagery is acknowledged. Without it memories of the lecture would surely have been flawed. Likewise, the QVMAG's publication relative to 'Tasmania's Forgotten Emu' has been an invaluable reference as it surely will be for anyone taking up the challenge to interrogate the lutruwita islands' CULTURALlandscaping. Likewise, the numerous 'corespondents' who have been involved in testing the cultural realities that inform Tasmanian 'placedness', and in an ongoing way, is much appreciated.

This reference has been created as a component of a research process built upon the foundation of 'open access critical review' supported as it is by 21st C communication paradigms. The 'Moral Rights' of the authors are acknowledged. The process is a deSILOING process that hopefully researchers will more often employ. Additionally, the methodology affords rhizomatic interfacing towards expanding the research networks.in play.

QVMAG PUBLICATION

Tasmanian Emu (Dromaius novaehollanddiae diemenensis)

at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery

No comments:

Post a Comment