BIOGRAPHY: Herman Jünger was born in Hanau 1928 and he died at the age of 76in his house in Pöring east of Munich In 1947, after his high school diploma in Hanau, Hermann Jünger graduated from the state academy of academies Hanau from 1947 to 1949 and graduated as a silversmith with the journeyman's examination ..... In the period from 1949 to 1962, Hermann Jünger worked in various workshops and factories in Bremen , Heidelberg , Ziegelhausen, Geislingen at the Steige ( WMF ) and at Wilhelm Wagenfeld .

BIOGRAPHY: Herman Jünger was born in Hanau 1928 and he died at the age of 76in his house in Pöring east of Munich In 1947, after his high school diploma in Hanau, Hermann Jünger graduated from the state academy of academies Hanau from 1947 to 1949 and graduated as a silversmith with the journeyman's examination ..... In the period from 1949 to 1962, Hermann Jünger worked in various workshops and factories in Bremen , Heidelberg , Ziegelhausen, Geislingen at the Steige ( WMF ) and at Wilhelm Wagenfeld .

During this period, he also finished his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich from 1953 to 1956 with Franz Rickert, and from 1953 to 1957 he produced designs in porcelain for the company Rosenthal . From 1956 to 1961 he ran his own workshop in Munich.

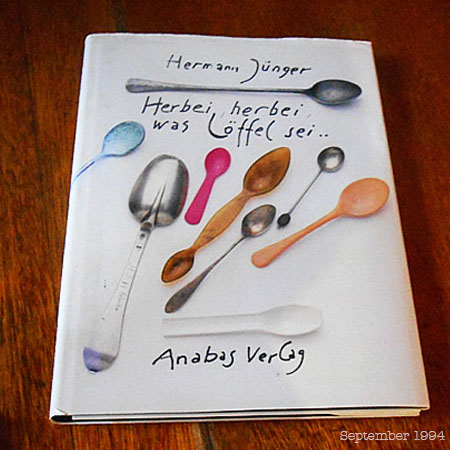

Herman Jünger has work in museums worlwide: Frankfurt, Hamburg, Hanover, Jablonec, Cologne, London, Melbourne, Munich, Perth, Pforzheim, Prague, Sydney. He is well known for his statement, "my statement is my jewellery". Likewise, his statement as a teacher are his students and as a collector what he had to say about collecting is his collections. Jünger's spoon collection quite apart from being an interrogation of the 'spoon form' it also interrogates 'materiality'. His book on his 'spoon collection' is an eloquent 'statement' that operates at many levels and that speaks of many things. Within this book Jünger explores the use of bone and horn in 'spoon making' and the narratives invested invested in a spoon and the horn and bone.

4

7

8

Similarly, in traditional Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi is centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The aesthetic is sometimes described as one of appreciating beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete" in nature. It is prevalent in many forms of Japanese cultural production.

Wabi-sabi is a composite of two interrelated aesthetic concepts, wabi and sabi. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- wabi may be translated as "subdued, austere beauty," while

- sabi means "rustic patina.

Characteristics of wabi-sabi aesthetics and principles include asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty, intimacy, and the appreciation of both natural objects and the forces of nature.

Wabi-sabi can be described as "the most conspicuous and characteristic feature of what we think of as traditional Japanese beauty. It occupies roughly the same position in the Japanese pantheon of aesthetic values as do the Greek ideals of beauty and perfection in the West."

Another description of wabi-sabi by Andrew Juniper notes that, "If an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi."

For Richard Powell, "Wabi-sabi nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.

When it comes to thinking about an English definition or translation of the words wabi and sabi Andrew Juniper explains that, "They have been used to express a vast range of ideas and emotions, and so their meanings are more open to personal interpretation than almost any other word in the Japanese vocabulary."

Therefore, an attempt to directly translate wabi-sabi may take away from the ambiguity that is so important to understanding how the Japanese view it.

No comments:

Post a Comment